Key Takeaway:

The more frequently and longer students spend time online, the lower the ratings of self-regulation in digital contexts. Yet, parental control and explicit teaching of digital skills can positively impact self-regulation. Technology in the classroom can enhance motivation, collaboration with peers, and engagement; however, it is not clear if the tools hamper skills like attention and self-regulation. —Frankie Garbutt

It is argued that social-emotional skills such as empathy, perspective, self-control and self-regulation are essential skills in the 21st century. However, one must consider how teaching these skills might need to be adapted at home and in school when today’s children have constant access to social media and the internet, requiring a new approach to self-regulation and self-control. The author of this study set out to find “what benefits for, and risks to, students’ cognitive and social and emotional skills are created by ubiquitous access.”

Self-rating is a means to examine the development of social-emotional skills. It “measures extraversion (sociability, engages in class activities), agreeableness (empathy, wants to help), conscientiousness (self-regulation, perseveres at activities), neuroticism (framed positively as emotional stability), and openness to experience (curiosity, appreciates new experiences).” Technology in the classroom can enhance motivation, collaboration with peers, and engagement, but it is not clear if the tools hamper skills like attention and self-regulation. At home, students’ use of digital tools is largely impacted by “time spent online, types of activities, and parental guidance.”

Changes in Self-Regulation and Social Skills Due to Technology Use

Initially, the results related to social skills showed a downward trend in the skills of self-regulation in digital and non-digital context, whereas the other skills seemed to not be affected because “ratings of the dimensions most clearly related to social skills, extraversion, and agreeableness did not have a consistent trend.“ The results of the study showed five trends:

- “Self-regulation in digital contexts was significantly lower (M = 3.05, UL = 3.19) than the equivalent measures in non-digital.“

- “This pattern of lower self-regulation in digital contexts compared with non-digital contexts was consistent across the ages.”

- “Ratings of social skills tended to be higher than those for self-regulation.”

- “Last, ratings of self-regulation in digital contexts appeared to be unrelated to personality dimensions and social skills generally.”

Implications for Schools

The authors discussed that schools can be beneficial when teaching children about self-regulation in a digital context because metacognitive skills and self-regulation are skills consistently taught, which can respectively support the students’ use of digital tools.

Moreover, “like self-regulation, the community of practice involving parents, teachers, and students had a focus on positive online interactions. In contrast, engaging in social media activities at home was associated with higher ratings of social skills in digital (but not in non-digital) contexts.”

Overall, schools are an environment in which students can learn valuable skills, such as self-regulation and social skills, in the ever increasing digital world when complimented by parental involvement and guidance at home. The authors suggest that further research should investigate how parents and schools can respectively support the building of these skills.

Summarized Article:

McNaughton, S., Zhu, T., Rosedale, N., Jesson, R., Oldehaver, J., & Williamson, R. (2022). In school and out of school digital use and the development of children’s self‐regulation and social skills. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 236-257.

Summary by: Frankie Garbutt – Frankie believes that the MARIO Framework encourages students to become reflective, independent learners who progress at their own rate.

Key Takeaway

Vocabulary and grammar instruction alone is not enough to become an expert in writing. Students that use self-regulation strategies exhibit increased writing skills and success. Specific self-regulation behaviors exhibited in the writing process can be classified into seven categories: regulation of environmental factors, regulation of sensory and motivational factors, planning, strategy development, regulation of temporal and social factors, monitoring, and evaluation. —Ayla Reau

Self-Regulation and Writing

Self-regulation is defined as the “whole of the thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that the individuals develop in order to” determine, and make the efforts needed, to reach goals. The current body of research suggests that vocabulary and grammar instruction alone is not enough to become an expert in writing, and that “use of self-regulation strategies is important and necessary for increasing writing success and performance.”

While current research has shown a strong relationship between self-regulation and writing skills, there is insufficient detailed research on which “behaviors exhibited in the writing process can be accepted as self-regulation skills.”

Therefore, the study by Sarikaya and Yılar seeks to identify in detail the “self-regulation behaviors exhibited by the 4th-grade students in the writing process within the scope of peer-assisted writing activities.”

Peer-Assisted Writing Study

A peer-assisted writing environment was used in this study to reveal students’ thinking styles and self-regulation behaviors, but the behaviors seen from this study can be transferred to independent writing. Peer-assisted writing can be defined as “the process in which students work together in pairs (in the context of writing) to plan, create, write and edit a story or text.”

The student participants exhibited self-regulation behaviors that could be classified into seven categories: “regulation of environmental factors, regulation of sensory and motivational factors, planning, strategy development, regulation of temporal and social factors, monitoring, and evaluation.”

The following section lists the behaviors the authors observed in their student participants in each of these categories. Teachers can guide and model to students how to use these strategies in writing in relation to self-regulation. In addition, writing interventions could also be developed around these specific skills or categories.

Results

The study observed behaviors for the regulation of environmental factors such as the student arranging or checking the lighting, temperature, and sitting position. When participants try to organize the physical environment before writing they are identifying and eliminating distracting factors to create a positive environment for writing to occur.

Behaviors for the regulation of sensory and motivational factors were observed, like subject interest, maintaining motivation, and rewarding oneself. Goal and target setting in particular is key to initiating the self-regulation process as goals serve as a way for students to continue to monitor and evaluate the entire writing process.

The study observed behaviors for planning-related self-regulation. For example, a student would focus on the purpose of writing, question the topic and text, or thinking about the story before and during writing. These behaviors enable students to self-organize their writing. Questioning of what is done and what to do next, along with accessing prior knowledge, all require self-regulation skills.

Strategy development behaviors were observed, including researching the topic, writing more legibly, paying attention to transitions, and others. “Strategy development behaviors are regarded as self-regulation skills in relation to writing action such as making plans to avoid deviating from the subject of writing, forming drafts in mind or by writing and sticking to this draft, paying attention to the harmony of ideas.”

Planning and using time effectively, and seeking help are behaviors related to temporal and social factors and require strategies for understanding and communicating.

The study observed the self-regulation behaviors related to monitoring. For example, students would review for typos, evaluate the level of writing, and check for clarity and adherence to the topic. The ability to follow the writing process with a self-developed monitoring mechanism (comparing their goals to their performance) requires advanced self-regulation skills.

Evaluation behaviors, like comparing performance and deciding if the goal is met, were identified during the writing process. “The process of reviewing, editing, decision making, judgment, and, accordingly, regulating the behavior of the writers are the integral parts of self-regulation.”

Summarized Article:

İsmail Sarikaya & Ömer Yılar (2021) Exploring Self-Regulation Skills in the Context of Peer Assisted Writing: Primary School Students’ Sample, Reading & Writing Quarterly, 37:6, 552-573, DOI: 10.1080/10573569.2020.1867677

Summary by: Ayla Reau—Ayla is excited to help continue to grow the MARIO Framework, seeing the potential for it to impact all students across any educational context.

Key Takeaway:

The change from onsite learning to online can cause students to lose motivation and efficiency in their learning. Having self-regulation skills and the use of preferred low or high-impact strategies can also affect student learning. It is crucial to understand these factors and support students by helping them with self-regulation skills and deciding on study strategies that work best for them. —Nika Espinosa

This study primarily focuses on the shelter-in-place adaptations of students in a doctor of chiropractic program. Forty-nine percent of the 105 students enrolled participated in the data collection. The researchers focused on primary study strategies, technology use, motivation and efficacy, study space and time, metacognitive planning, monitoring, and evaluating. Part of the study required the participants to give sufficient evidence.

Primary Study Strategy

When it comes to study strategies, the most frequently chosen study strategy by the students was repeated reading (low-impact) and completing practice problems (high-impact). A majority of the respondents (82%) did say that they didn’t use the same strategies during shelter-in-place that they used when they were onsite learning. Low-impact strategies such as highlighting and memorizing were frequently chosen by the respondents, whereas high-impact strategies were not as preferred. The survey also showed that the chosen primary strategies that participants used were low-impact. “These data imply that although a student selects a high- or low-impact study strategy from a list, it may not reflect the true study approach but rather indicate the 1st step in the approach.“

Technology Use

A majority of the students (86%) reported that there wasn’t much difference in their use of technology when the switch to shelter-in learning was made. Twelve out of the fifty-two students did say their adaptations to technology were more significant.

Study Space

“Sixty-one percent (31/51) of respondents indicated a range in level of challenge and adaptability in finding a new study space.” Part of the challenges included not having a separate work-home space, noise, and distractions, and a lack of social interaction to support learning. “Eight respondents who selected low-impact study strategies and 4 respondents who selected high-impact study strategies as their primary strategy described positive adaptations.”

Study Time

“Ninety-four percent (48/52) of respondents reported that they did not use the same amount of time studying during shelter-in-place orders as in prior academic terms in the program.” The biggest influencers were motivation and efficiency. Students’ motivation had gone down due to reasons such as pandemic stressors, lack of social interaction, and the structural shift in teaching and learning. Some reported that the work-life balance had become difficult, and a few students mentioned only finding accountability in deadlines and that their motivation was only to pass. Some students however became more efficient in their studies when they found ways to manage their own time.

Planning as a Metacognitive Strategy

Eighteen of the participants said that the most common plan they used during shelter-in learning was to create task lists and a study space to structure their learning. All of the participants that provided evidence also said that in order to set new goals, they needed to use high-impact strategies, regardless of if their primary strategy was low or high impact. “Forty-five percent (14/31) of respondents who selected a low-impact study strategy as their primary strategy described a positive or solutions-oriented plan moving forward, while 71% (15/21) of respondents who selected a high-impact study strategy as their primary strategy described a positive or solutions-oriented plan moving forward.” Those who did not provide sufficient evidence described the challenges of remote learning.

Monitoring as a Metacognitive Strategy

A majority of the participants provided evidence for monitoring their learning. Some of them however mentioned decreased confidence in studying due to either pandemic stressors or the lack of hands-on experience. A student was quoted that they relied very much on the school structure for learning. Uncertainty about the impact of their study habits was mentioned by six of the participants.

Evaluating as a Metacognitive Strategy

Seventy-seven percent of the participants expressed that high-impact strategies were more effective, but the rest described resorting to low-impact strategies due to pandemic stressors.

Summarized Article:

Williams, C. A., Nordeen, J., Browne, C., & Marshall, B. (2022). Exploring student perceptions of their learning adaptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Chiropractic Education. https://doi.org/10.7899/jce-21-11

Summary by: Nika Espinosa – Nika believes that personalized learning is at the heart of special education and strives to collaborate with educators in providing a holistic, personalized approach to supporting all learners through the MARIO Framework.

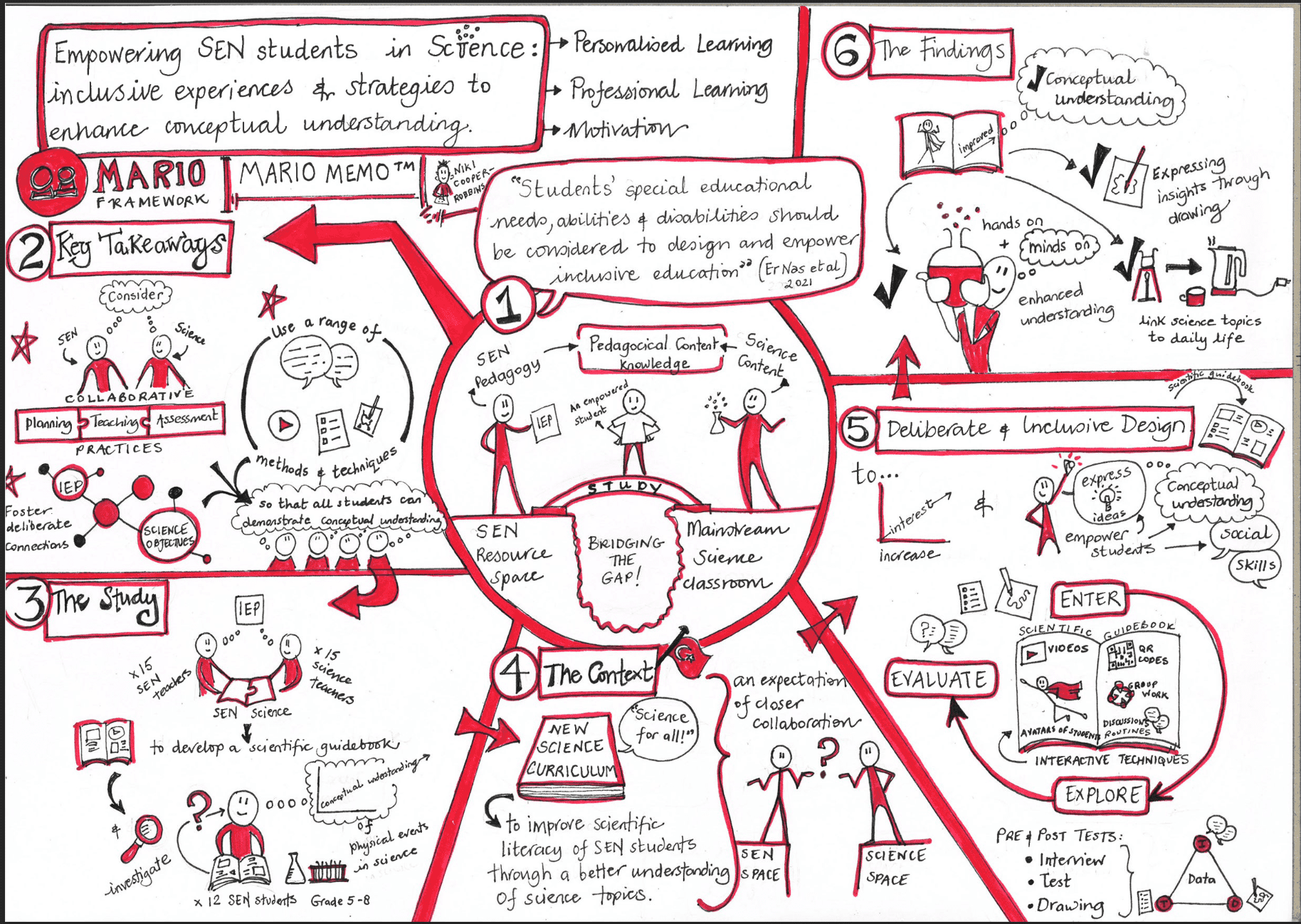

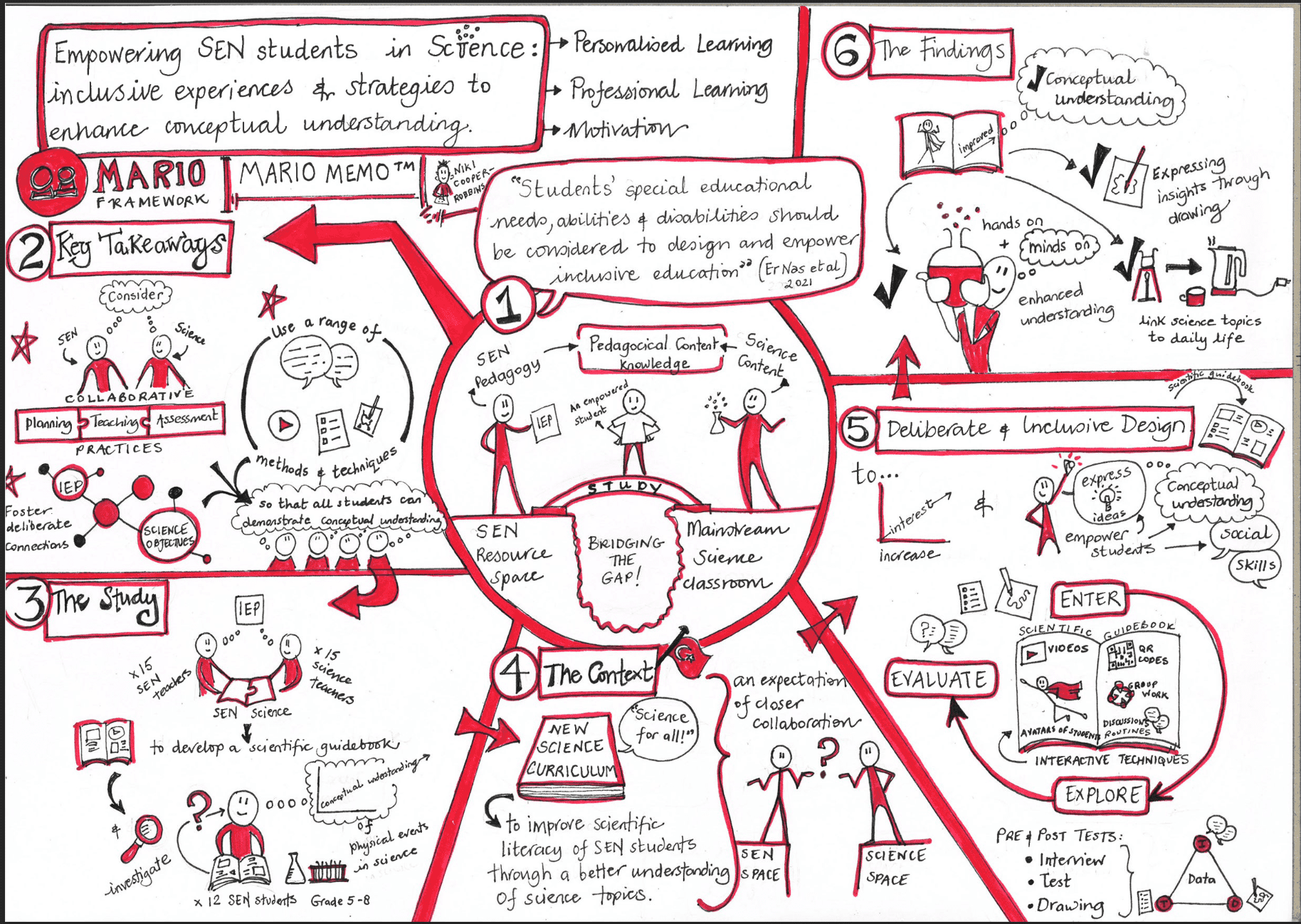

Key Takeaway:

As educators, we must consider our collaborative planning, teaching, and assessment practices for Special Educational Needs (SEN) students to establish a deliberate connection between their Individual Education Program (IEP) and mainstream science objectives. In the science classroom, this might include using a range of methods, techniques and strategies that will enable all students to demonstrate their conceptual understanding of science as well as to build interest and confidence in the subject. —Niki Cooper-Robbins

Scientific Literacy for SEN Students

This article outlines a Turkish study conducted with 12 grade 5-8 SEN students and the contributions of 15 science and SEN teachers. The aim of the study was to:

- develop a scientific experimental guidebook for the students;

- investigate the book’s effect on the students’ conceptual understanding of physical events in science.

The study took place against an identified, national need to improve the scientific literacy of SEN students through a better understanding of science topics. The launch of a new curriculum brought with it an expectation of closer collaboration between the science and SEN teachers. The importance of this research becomes apparent when you come to realize that in this context, it is the norm for SEN students to receive their Turkish, math, and science education in the separate SEN resource space as opposed to the mainstream classroom. “Resource rooms take mainstream students’ learning needs into consideration,” and this was the missing element (excuse the pun!) in the science classroom. In contrast, the science teachers had the subject knowledge, but the SEN teachers did not. The purpose of the scientific experimental guidebook was to bridge the gap referred to as ‘pedagogical content knowledge’ between the SEN and science environments.

Deliberate & Inclusive Design

The guidebook incorporated interactive techniques to increase interest in and attitudes towards science and to empower students to express, support and generate their ideas in a range of ways. Avatars of the students and QR code links to YouTube videos of experiments were designed to build confidence, interest and belonging. Discussion-based routines to support the introduction, exploration and evaluation of concepts played a key role in the simultaneous development of conceptual understanding and social skills.

Findings

The results of the study showed that the guidebook was successful in that it did support conceptual understanding in a positive way. The data revealed that the “hands-on and minds-on” experiences enhanced understanding, and the option to express insights through drawings proved more successful than the tests and interviews. When considering why, the reason given was the students’ complex and varying profiles. For example, students with dyslexia or dysphasia were less inhibited when conveying understanding through drawings as opposed to writing or speech.

The study identified that the students struggled to transfer knowledge to new situations, and this was particularly evident with the more abstract concepts. The main finding, therefore, was that learning was more effective when the learning experiences were multi-sensory and interactive.

In addition, the study was found to be “in harmony with Dilber’s (2017)1 views, emphasizing that science topics should be contextually linked with daily life … Moreover, such a learning environment (i.e. conducting science experiments within small groups, watching experimental videos, and discussion about the results) may have enabled [SEN students] to imagine the concept in their minds.2 This means that peer learning and effective teaching strategies overcome students’ difficulties in understanding science concepts.”3

Summarized Article:

Er Nas, S., Akbulut, H. İ., Çalik, M., & Emir, M. İ. (2021). Facilitating Conceptual Growth of the Mainstreamed Students with Learning Disabilities via a Science Experimental Guidebook: a Case of Physical Events. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-020-10140-3.

Summary by: Niki Cooper-Robbins—As an ESL Coach, Niki is an advocate for the needs of language learners and, through the MARIO Framework, endeavors to nurture and celebrate linguistic diversity in education.

Additional References:

- Dilber, Y. (2017). Fen bilimleri öğretmenlerinin öğrenme güçlüğü tanılı kaynaştırma öğrencileri ile yürüttükleri öğretim sürecinin incelenmesi / Examination of the instructional process carried out by the science teachers with mainstreaming students diagnosed learning disabilities [Unpublished Master’s thesis]. University of Karadeniz Technical.

- Talbot, P., Astbury, G., & Mason, T. (2010). Key concepts in learning disabilities. Sage.

- Thornton, A., McKissick, B. R., Spooner, F., Lo, Y., & Anderson, A. L. (2015). Effects of collaborative pre-teaching on science performance of high school students with specific learning disabilities. Education and Treatment of Children, 38(3), 277–304. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2015.0027.

Key Takeaway:

School-wide interventions that reduce bullying can also reduce school attendance problems. Interventions in this area should also be targeted towards autistic youth as they experience a high rate of school refusal linked to the bullying occurring in school settings. Identification of attributes such as the ability to maintain control when angry and the ability to control negative thoughts can help protect this population from school refusal and may be a potential pathway for effective interventions.—Ayla Reau

School Refusal

School refusal (SR) is “characterized by a young person’s reluctance or refusal to attend school in conjunction with emotional distress.” This is typically measured on a threshold for absence or difficulty attending over a certain period. Emerging school refusal (ESR) is the term used to describe the period before these thresholds are reached. Absence from school can negatively impact “academic achievement and socio-emotional outcomes, contribute to family stress, and place extra burden on school staff,” so early intervention is key for students exhibiting ESR.

Bullying, ASD, and Psychological Resilience

It is widely accepted that being bullied is associated with SR in youth. Youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are especially vulnerable to bullying in mainstream settings, which could explain the “high rate of SR among autistic youth.” Therefore, there is a need for interventions that reduce SR and ESR among bullied youth.

“Psychological resilience refers to an individual’s capacity to resist the harmful effects of adverse stressors and to resume functioning despite them.” It has been associated with “reduced anxiety and depression among autistic boys, parents who have an autistic child, and non-autistic siblings of a young autistic person.” The current study focuses on the link between psychological resilience and ESR in bullied autistic youth, and data was collected through an online questionnaire completed by 58 young autistic males.

Major Findings

- 56% of bullied autistic youth asked their parents to stay home from school because of bullying (ie. displayed ESR).

- A significant inverse relationship (one increases, the other decreases) was found between ESR and two aspects of psychological resilience: the ability to maintain control when angry and the ability to control negative thoughts.

- No statistical relationship was found between psychological resilience and ESR in elementary school children.

Overall, the “identification of attributes that can help protect bullied autistic youth from engaging in school refusal may be a potential pathway to effective interventions for these young people.” Further studies are needed to determine whether psychological resilience acts as a protective factor against ESR and SR in bullied autistic youth and/or whether the experience of bullying leads to increased resilience and a decreased likelihood of SR happening over time. Regardless, educators and school administrators should carry out school-wide interventions that reduce bullying in order to reduce school attendance problems and foster a sense of well-being and safety at school.

Summarized Article:

Bitsika, V., Heyne, D. A., & Sharpley, C. F. (2022). The inverse association between psychological resilience and emerging school refusal among bullied autistic youth. Research in developmental disabilities, 120, 104121.

Summary by: Ayla Reau—Ayla is excited to help continue to grow the MARIO Framework, seeing the potential for it to impact all students across any educational context.

Key Takeaway:

Common training procedures proved effective for training preschool teachers to collect progress monitoring data, an essential skill for teachers, especially those working within the implementation of multi-tiered support systems. While teachers acquired, maintained, and generalized data collection procedures, they did not implement these procedures outside study sessions, highlighting the importance of top-down scaffolds to ensure regular implementation of progress monitoring. – Ashley Parnell

Progress Monitoring

“Progress-monitoring is an essential skill for teachers serving children for whom the general curriculum is insufficient.” “The reason for progress monitoring is simple: it gives you data to measure whether the intervention or instruction a student is receiving is actually helping them close gaps in their learning”.1

Increased adoption of multi-tiered systems of supports (MTSS) across education programs heightens the need for feasible, routine, and reliable data collection systems. In turn, identifying effective methods for training teachers to implement data collection is crucial.

The Study

In response to this need, the current study evaluated the effects of a training package on teacher implementation of data collection procedures in inclusive preschool classrooms.

Two teachers (one lead and one assistant) per class in two different classrooms were trained to implement a teacher-directed behavioral observation (TDBO) data collection, which involved:

- Securing student’s attention

- Presentation of demand or question

- Absence of any form of prompting

- Provision of specific praise of correct response or ignoring/responding neutrally to errors.

- Scoring of each trial as correct or incorrect.

Each teacher was assigned three children in their respective classroom. All children scored in the bottom 25% of their class on the Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System (AEPS), a criterion-based assessment, in one of the following areas: concepts, premath, or phonological awareness and emergent reading. Using the AEPS assessment data, one behavior/skill and 5-10 related targets were identified for each child (e.g., labeling of letter sounds, letter A-J; counting objects, numbers 1-5).

Teacher training package consisted of: 1) a video-based multimedia presentation, 2) a single-page hand-out describing each TDBO procedure, and 3) structured feedback following each training session. Sessions took place in the classroom setting 4 days per week (3 sessions per day with each child assigned to them) for 3 months. Teachers selected the materials and activity in which they collected data on the child’s target skill. Generalization data were collected throughout the study, with the exception of participants that mastered the material during the skill acquisition phase.

Results and Implications

Results suggest:

- Commonly used teacher training practices are functionally related to teacher mastery of TDBO procedures for collecting data on child progress within inclusive preschool classrooms.

- Generalization probes indicated that teachers may be able to implement and maintain the procedures with fidelity across children and skill types.

- Teachers reported never using the data collection procedures outside of study sessions.

Implications to practice include:

- Lack of data collection outside sessions highlights the need for stakeholders within MTSS models to consider a systems-level approach to development and implementation, as training alone will likely be insufficient in ensuring implementation if there is no oversight.

- Initial lectures in teacher training are almost always conducted in person. Technology can be leveraged successfully to improve common teacher training practices and reduce in-person training time, promoting accessibility, and flexibility (i.e., video-based multimedia presentation).

Summarized Article:

Shepley, C., Grisham-Brown, J., Lane, J. D., & Ault, M. J. (2020). Training Teachers in Inclusive Classrooms to Collect Data on Individualized Child Goals. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 0271121420915770.

Summary by: Ashley M. Parnell — Ashley strives to apply the MARIO Framework to build evidence-based learning environments that support student engagement, empowerment, and passion, and is working with a team of educators to grow and share this framework with other educators.

Academic researcher Collin Shepley participated in the final version of this summary.

Additional References:

- Spruell, F. M. (2021, June). Progress monitoring for MTSS at the secondary level. Branching minds. https://www.branchingminds.com/blog/progress-monitoring-secondary-level-mtss

Key Takeaway:

It can be tempting to implement rewards and punishment in the classroom and educators tend to forget about the importance of intrinsic motivation to foster academic growth and engagement. Shkedy et al. (2021) explored how implementing Visual Communication Analysis (VCA) along with self-determination theory when teaching students to type independently may provide an avenue to build intrinsic motivation among students with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities. Consequently, the learning and functional communication skills of these students would improve. —Michael Ho

The Study

Shkedy et al. (2021) examined the efficacy of using Visual Communication Analysis (VCA) in teaching children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual disability (ID), and speech and language impairment to type independently as a means of expressive and functional communication. VCA is an “experiential therapy that is used to teach communication and can also be used to teach academics, while building confidence and self-esteem, and ultimately decreasing maladaptive behaviors.” In this study, Shkedy et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between instructional time each student received in typing and the letters correct per minute.

The researchers hypothesized that VCA implementation will increase psychological well-being and decrease maladaptive behaviors among children with ASD, ID, and speech and language impairment.

Major Takeaways

- “The rise in the number of students with disabilities served under the federal law of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in public schools increased between 2011 and 2017, from 6.4 million to 7.0 million students.”1

- Students with ASD and ID have been significantly increasing over the past few years, and there is a need to provide personalized support to each student based on their needs and abilities.

- “Special education classrooms are usually very structured and rigid and the majority are managed using token systems,” indicating that there is very little autonomy in a special needs classroom. This contradicts what special educators are responsible for—to meet the needs of each unique learner.

- VCA has led to significant decreases in maladaptive and self-injurious behaviors, an increase in verbalizations and effective toilet training.

- VCA combines Self-Determination Theory (SDT) with visual support, prompting, and technology; it provides students a variety of choices and perceived control when learning, in order to develop intrinsic motivation and competence.

- Deci and Ryan (1985a & 2000) defined Self-Determination Theory (SDT) as a theory of intrinsic motivation that has three components—autonomy, competence, and relatedness; these three components tend to foster motivation and engagement for activities, including enhanced performance, persistence, and creativity.2

- 27 students aged 5.5 to 11.5 years, who had at least one diagnosis of ASD, ID, speech-language impairment, were recruited from three special day classrooms across two elementary schools in South Bay Union School District, San Diego County, California.

- On average, a minimum of one class period per school day was allocated to using VCA, and data was automatically collected by a software. Based on self-determination theory, the students were provided choice, autonomy, and competence at the appropriate level without any rewards or punishments.

The Findings

- The results indicated that there was a consistent positive effect of VCA-based instruction on typing efficiency for all groups of students (ASD, ID, speech-language impairment, and autism comorbid with ID), regardless of the diagnosis.

- With the use of VCA, participants learned to type effectively, thereby improving their learning and functional communication skills. In addition, participants found success with learning novel tasks, as the difficulty of the task gradually increased after each successful performance.

- Educators, professionals, and parents can use the data from this research to create opportunities for children with ASD, ID, and/or speech-language impairment to design and implement effective instruction on communication through typing.

Limitations

Firstly, the time dedicated to the study varied from one student to another based on teachers’ expectations. There is also a lack of standardized assessments used prior to the beginning of this study, as age limitations on some assessments meant that younger participants were given different assessments from older participants. In addition, the age range of the participants ignored older students from secondary schools. Finally, less than 25% of the participants were females.

Summarized Article:

Shkedy, G., Shkedy, D., Sandoval-Norton, A. H., Fantaroni, G., Montes Castro, J., Sahagun, N., & Christopher, D. (2021). Visual Communication Analysis (VCA): Implementing self-determination theory and research-based practices in special education classrooms. Cogent Psychology, 8(1), 1875549.

Summary by: Michael Ho—Michael supports the MARIO Framework because it empowers learners to take full control of their personalized learning journey, ensuring an impactful and meaningful experience.

Academic researchers Dalia Shkedy and Aileen Herlinda Sandoval participated in the final version of this summary.

Additional References:

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Children and youth with disabilities. U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Cognitive evaluation theory. In Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior (pp. 43–85). Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7_3

Key Takeaway:

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is necessary for the academic achievement of a student and for their future success in many aspects of their lives. Ensuring that SEL is taught with fidelity is a goal for many schools and depends not only on instructional support, but other factors such as years of teaching, and rigorous classroom management. —Shekufeh Monadjem

The Importance of Social and Emotional Learning

Students learn best when they are in a caring and safe environment, where they have trusting relationships with their teachers and peers. These relationships promote the development of social and emotional skills that are crucial for “academic achievement and life success.”1 In their study, Thierry, Vincent, and Norris (2022) explained that in order to foster social and emotional learning (SEL) among students, they suggest using the National Commission on Social, Emotional and Academic Development’s (2018) recommendations for districts and schools. One of these recommendations is the adoption of an evidence-based SEL curriculum for the explicit instruction of social and emotional skills.

The Importance of Using Fidelity When Implementing Curriculum

One major factor to consider when introducing a new curriculum is ensuring that it is being used with fidelity, in order for students to make the maximum gains. A number of research reviews confirm that SEL curricula when implemented with “high levels of fidelity are more likely to improve students’ social-emotional competence and academic performance.”2

Other important factors are the socio-emotional competency levels of teachers and their ability to build positive relationships with students. This is based on five core competencies:

- Self-awareness

- Self-management

- Social awareness

- Relationship skills

- Responsible decision-making

Building positive relationships with students requires teachers to be skilled in all competencies.

Methodology

Sixty pre-kindergarten to 1st-grade teachers participated in this US-based study from 7 schools. 52% of the participants were African-American, 30% White, and 18% Hispanic. The following teacher-level predictors were examined over the period of the first month in which the curriculum was implemented: “1) teacher demographics, including ethnicity/race and years of teaching experience; 2) self-efficacy for managing classroom behavior; 3) emotional support; 4) classroom organization; and 5) instructional support.”

The scoring system used was the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS), which has shown to be a valid and reliable tool that “essentially operationalizes positive teacher-student relationships according to specific interactions that teachers have in capturing the following three domains of teacher-student interactions: (1) emotional support, (2) classroom organization, and (3) instructional support.”3 Independent observers assessed teachers on these interactions during the initial month of the curriculum.

Findings

Teachers with “greater pre-implementation classroom management self-efficacy and more teaching experience had higher adherence to the curriculum” and therefore had higher levels of fidelity. Hispanic teachers who taught bilingual classes were less likely than White, non-Hispanic teachers to adhere to the curriculum schedule, as they needed more implementation support to match their caseload. Instructional support proved to be the only positive predictor of the quality of lesson delivery.

Limitations of the Study

One limitation of the study was the small sample size, and another was that only the initial fidelity of the first month of the implementation of the curriculum was measured, not the long-term delivery.

Summarized Article:

Thierry, K. L., Vincent, R. L., & Norris, K. (2022). Teacher-level predictors of the fidelity of implementation of a social-emotional learning curriculum. Early Education and Development, 33(1), 92-106.

Summary by: Shekufeh Monadjem – Shekufeh believes that the MARIO Framework builds relationships that enable students to view the world in a positive light as well as enabling them to create plans that ultimately lead to their success.

Additional References:

- Jones, D. E., Greenberg, M., & Crowley, M. (2015). Early social emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2283–2290.

- Derzon, J. H., Sale, E., Springer, J. F., & Brounstein, P. (2005). Estimating intervention effectiveness: Synthetic projection of field evaluation results. Journal of Primary Prevention, 26(4), 321–343.

- Burchinal, M., Vandergrift, N., Pianta, R. C., & Mashburn, A. J. (2010). Threshold analysis of association between child care quality and child outcomes for low-income children in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(2), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.10.004

Key Takeaway:

Students with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD) face an increased risk of mental health issues and behavior-related disciplinary action, impacting their academic success. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these risks have been significantly exacerbated due to physical and social isolation. Educators working to support students with EBD must adapt their methods of instruction and communication in order to provide consistent and effective services. Thus, educational policies and guidelines must be re-evaluated to reflect the new challenges brought forward by virtual learning environments. — Taryn McBrayne

Pandemic Effects on Students with EBD

In the United States, “5% of all students with disabilities receiving special education services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) fall under the disability category of emotional disturbance.”1 Students with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD), “are significantly more likely to be suspended, expelled, and arrested than their peers without IEPs and with IEPs for other disabilities.”2 As a result, students exhibiting EBD and who have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) often have access to intensive behavior interventions and support plans that are managed by special education teachers. However, following the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, many schools closed, “potentially exacerbating the risk factors experienced by students with EBD.”

Following the closure of schools, districts needed to determine new policies regarding how students with an IEP would receive the support and services that they are legally entitled to. While technology aided in the provision of these services, those with limited access to technology (i.e., lower bandwidth, lack of access to appropriate devices) may have had compromised access to services, resulting in a negative impact on learning.3,4

Hirsch et al. “surveyed special education teachers (SETs) and resource specialist program teachers (RSPs) who were serving students with EBD in spring 2020” in order to “gather information about the extent to which these educators delivered the various supports and interventions delineated in students’ IEPs during school site closures.” Survey respondents represented 35 states, the majority of whom reported working in public schools.

The results of the survey can be summarized as follows:

Communication Resources

- “Virtual meetings using platforms like Zoom were the most frequently (37.9%) used by all educators,” followed by telephone conferences and virtual classroom platforms such as Google Classroom and Seesaw. The chosen platforms varied based on district and individual school policy.

- It was unclear what activities were conducted via these communication channels and to what extent students were able to receive academic instruction through these platforms.

Intervention Strategies

- “Over half of respondents who were delivering optional or mandatory remote instruction indicated that they checked in with all of their students with EBD regarding their social, emotional, and behavioral well-being during school site closures.”

- Additional commonly reported strategies included “prevention strategies, reinforcement, and structured social skills activities.”

- Implementation of certain intervention strategies may have been contingent on the ease of virtual delivery.

- “Anecdotal parent reports via email or phone call” were reported as the most common form of assessment data to measure student progress. These assessments were largely collected by SETs in comparison to RSPs.

Implications

The authors of the article acknowledge that because the survey was conducted during the midst of the pandemic, their study is not without limitations. Some of the limitations mentioned in the article include: lack of a fully representative sample, reduced list of intervention strategies provided in the survey questions, and a reliance on respondent self-reporting.

Despite these limitations, Hirsch et al. propose “numerous practical, policy, and research implications and directions for future research.” The authors call on policy-makers and educational leaders to develop specific “guidelines for mandating and supporting continuity of instructional services particularly for students with disabilities during school site closures.” They also suggest that gaps in access to technology need to be addressed to prevent an increasing “homework gap” for those learners who do not have the capability to complete tasks as a direct result of poor internet access. Furthermore, while the results of the study suggest that student well-being check-ins were prioritized, some respondents admitted to not checking in with their students at all, prompting a re-evaluation of communication methods during virtual learning.

Summarized Article:

Hirsch, S. E., Bruhn, A. L., McDaniel, S., & Mathews, H. M. (2022). A Survey of Educators Serving Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disorders During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Disorders, 47(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/01987429211016780

Summary by: Taryn McBrayne — Taryn believes in the power of student voice and, through the MARIO Framework, strives to create more opportunities for both educators and students to regularly make use of this power.

Additional References:

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). Children and youth with disabilities. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

- Lipscomb, S., Haimson, J., Liu, A. Y., Burghardt, J., Johnson, D. R., & Thurlow, M. L. (2017). Preparing for life after high school: The characteristics and experiences of youth in special education. Findings from the National Longitudinal Transition Study 2012: Vol. 1. Comparisons with other youth (NCEE 2017-4016). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

- Kormos, E. (2018). The unseen digital divide: Urban, suburban, and rural teacher use and perceptions of web-based classroom technologies. Computers in the Schools, 35(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2018.1429168

- Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Potter, J. (2020). Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1761641

Key Takeaway:

Social and emotional learning (SEL) should be explicitly taught in schools, especially in secondary schools. SEL competencies can lead to improved peer relationships, heightened resilience, and a more positive school climate among secondary school students. It also empowers students who have been subjected to varying degrees of peer victimization. —Shekufeh Monadjem

The Benefits of Social-Emotional Learning

Social and emotional learning (SEL) strives to create “a preventative school-based framework which aims to promote resiliency and a positive school climate,” and is quickly becoming an essential part of school curricula.1 “Teaching SEL skills to youth within schools has been linked with increased social skills, academic performance, and reduced mental health problems and behaviour problems among students.”2

This study by Fredrick and Jenkins (2021) sought to examine the relationship between student perception of SEL skills taught through SEL instruction and peer relationships. 228 racially diverse participants from Grades 8-12 were included in the study.

The Benefits of Explicit SEL Instruction

Results showed that “SEL instruction was positively related to student SEL skills and positive perceptions of peer relationships, and the strengths of these associations were similar across boys and girls. In addition, these associations were similar for youth experiencing low, moderate, and high levels of victimization, but were especially robust for the high-victimization group.”

In addition to promoting student SEL skills, another purpose of SEL instruction is to “promote positive peer relationships and this may be especially important among high school students, given the value that adolescents place on friendships.”3 A critical aspect of school climate and culture are students’ perceptions of whether classmates treat each other with respect and inclusivity. Positive peer relationships are more evident in schools and classrooms where “teachers and staff provide social-emotional support, utilize curricula and activities which foster social interactions, and where adults model respectful and caring behaviour.”3 Research has supported a link between the teaching of SEL skills and positive peer relationships, as well as a reduction in aggressive behaviour and homophobic name-calling.

Previous research had shown that efforts to promote a positive school climate may have been harmful to students who continued to experience peer victimization.3 In contrast to previous research, findings from the current study revealed that SEL instruction was positively related to heightened SEL skills and positive peer relationships for both boys and girls, and these findings were more robust for students experiencing high levels of peer victimization.

Summarized Article:

Fredrick, S. S., & Jenkins, L. N. (2021). Social Emotional Learning and Peer Victimization Among Secondary School Students. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1-11.

Summary by: Shekufeh Monadjem – Shekufeh believes that the MARIO Framework builds relationships that enable students to view the world in a positive light as well as enabling them to create plans that ultimately lead to their success.

Additional References:

- Shek, D. T., Dou, D., Zhu, X., & Chai, W. (2019). Positive youth development: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 10, 131–141.

- Bear, G. G., Yang, C., Mantz, L. S., & Harris, A. B. (2017). School-wide practices associated with school climate in elementary, middle, and high schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 372–383.

- Bear, G. G. (2020). Improving school climate: Practical strategies to reduce behaviour problems and promote social and emotional learning. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Garandeau, C. F., Lee, I. A., & Salmivalli, C. (2018). Decreases in the proportion of bullying victims in the classroom: Efects on the adjustment of remaining victims. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416667492